What can and can’t publication data from the online database RICYT tell us

Alejandro Uribe Tirado

Few weeks ago, the Red de Indicadores de Ciencia y Tecnología (“Network of Science and Technology Indicators”) [RICYT by its Spanish initials] announced that “Updated statistical information it’s already available, obtained from RICYT’s last data survey. The main science and technology indicators from the countries of the region are included. Available information consists of 65 indicators that are given in a comparatively way and by country, comprising: Context Indicators, Input Indicators, Graduates, Patent Indicators and Bibliometric Indicators.”

This database provides information as of 1990 until 2016. First of all, it should be recognised the value of having such source of information as well as the fact that enables us to identify each country, and compare different standardised indicators. The more information we have from different sources, the greater the possibilities will be to have a holistic picture of our scientific output.

Here, I propose a general reflection on what these available data can and can’t tell us. This is interesting in order to understand visions and results of scientific communication in our Latin American context, comparing our countries with one other but also comparing them with others such as Canada, Spain, the United States and Portugal which are included in RICYT’s data.

Firstly, it’s worth mentioning the 14 databases from which RICYT gathers information about publications:

- Publications in Science Citation Index (SCI)

- Publications in SCOPUS

- Publications in Pascal

- Publications in INSPEC

- Publications in COMPENDEX

- Publications in Chemical Abstracts

- Publications in BIOSIS

- Publications in MEDLINE

- Publications in CAB International

- Publications in ICYT

- Publications in IME

- Publications in PERIODICA

- Publications in CLASE

- Publications in LILACS

We quickly note that there are other databases missing, which have been and are key in the region’s scientific communication. For instance, REDALYC (with 1.276 journals at present) or SCIELO (with 1.464 journals at present), which together with others in the region have done a significant work for years. They’ve encouraged a fundamental feature of our scientific communication—Open Access:

“Latin America is the most advanced region from the globe in adopting open access for its scientific and scholarly journals, which most of them are provided at full text online, free of charge for readers and authors, increasing significantly the visibility and accessibility to the region’s scientific production. This open access movement for the region’s journals was primarily launched by the regional initiatives SciELO, Redalyc, and the portal of portals, Latindex, and recently, the journal collections in open access institutional digital repositories” (Alperin, J, P., & Fischman, G. 2015).

We could also think of adding DOAJ since this database has, in the last years, purified its criteria so that current journals meet more quality requirements, and currently reports more than 2.000 journals from the region: Brazil (1274), Colombia (307), Argentina (191), Mexico (121), Chile (99), Cuba (77), Costa Rica (51), Peru (43), Ecuador (43), Venezuela (28), Uruguay (17), and so on.

These 14 databases aim to give a vision from different fields. But there are more missing that could give room to more determined fields and to interdisciplinarity. If we revisit the “Servicios de Indexación y Resumen” [Indexing and Overview Services] —SIRes— by OCYT for Colciencias, Colombia (2017), 61 SIRes are recognised, so in order to have a more comprehensive picture we’d be lacking other databases aside from SCIELO and REDALYC, which would be classified at a field of knowledge level, as general ones.

When interacting with dynamic data much information may be identified from these databases for the region and each country, as well as publication cross-reference data with other important variables in science and technology:

- Publications in SCI per habitant

- Publications in SCOPUS per habitant

- Publications in PASCAL per habitant

- Publications in SCI in relation to PBI

- Publications in SOCPUS in relation to PBI

- Publications in PASCAL in relation to PBI

- Publications in SCI in relation to I+D expenditure

- Publications in SCOPUS in relation to I+D expenditure

- Publications in PASCAL in relation to I+D expenditure

- Publications in SCI for every 100 researchers

- Publications in SCOPUS for every 100 researchers

- Publication in PASCAL for every 100 researchers

- Publication percentage in SCOPUS according to field

- Publications in SCOPUS in international collaboration

- Publications in SCOPUS in international collaboration according to field

Nevertheless, for this reflection and considering the necessity to include other sources of information, we’d like to highlight the following:

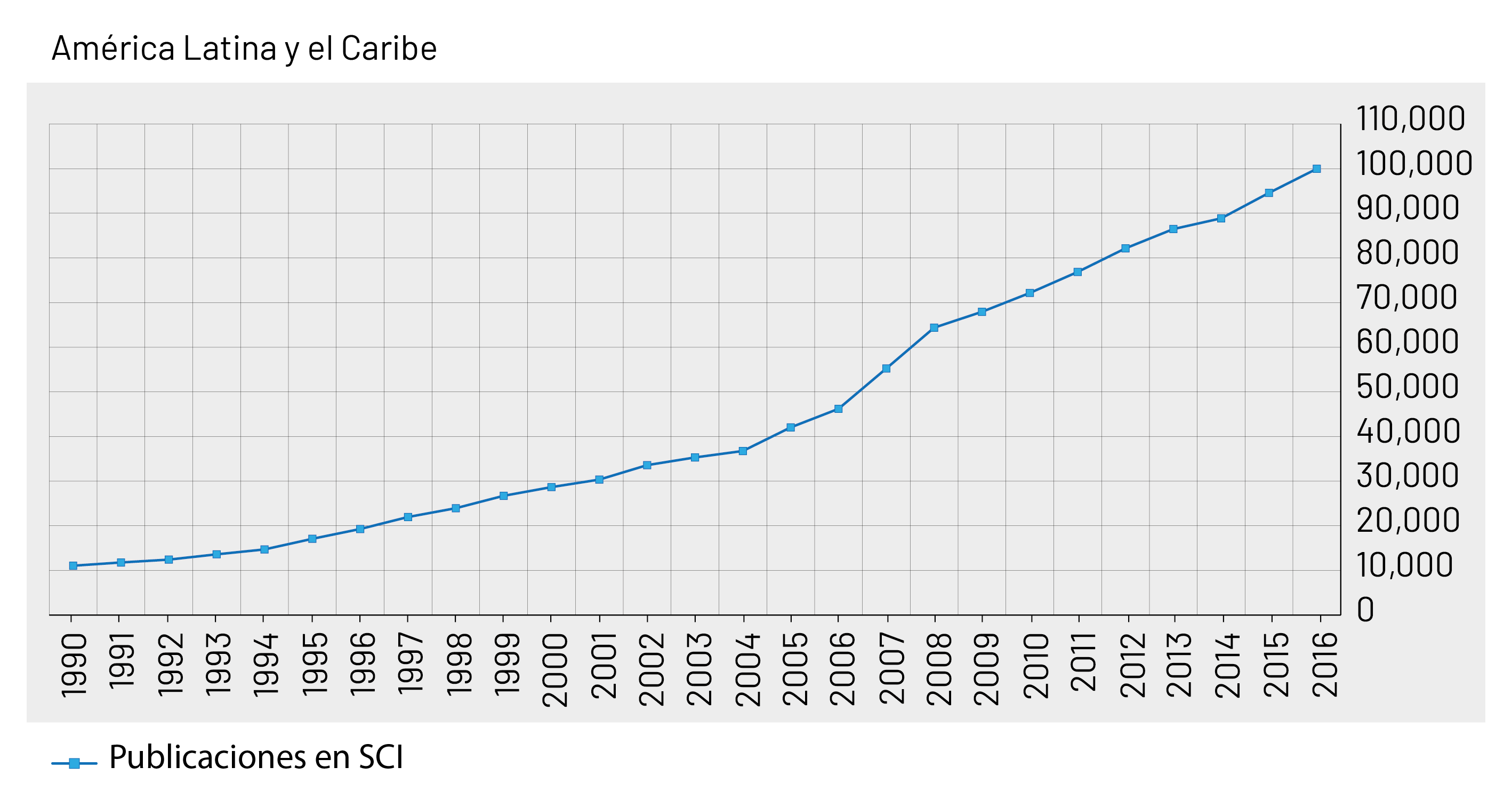

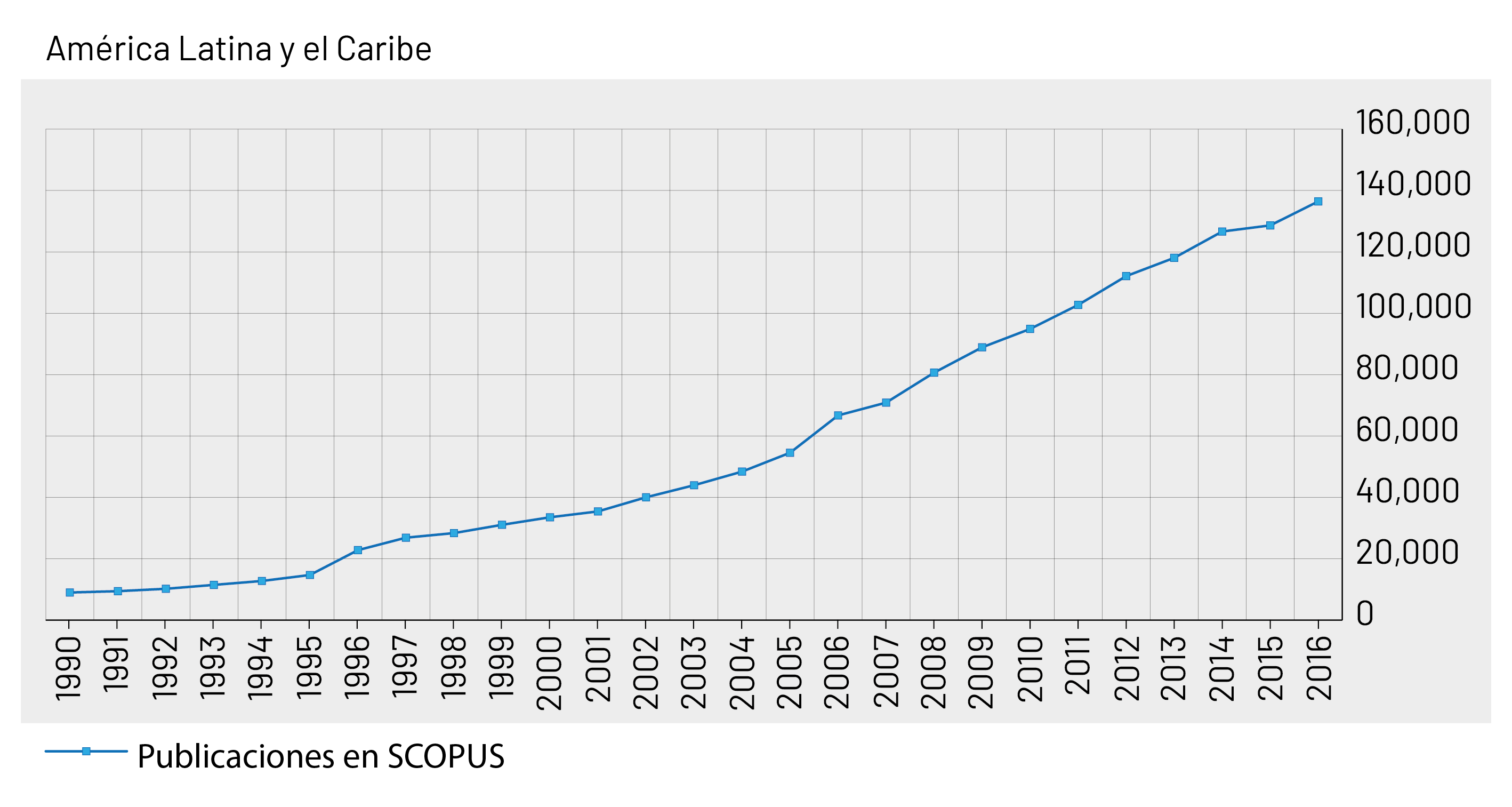

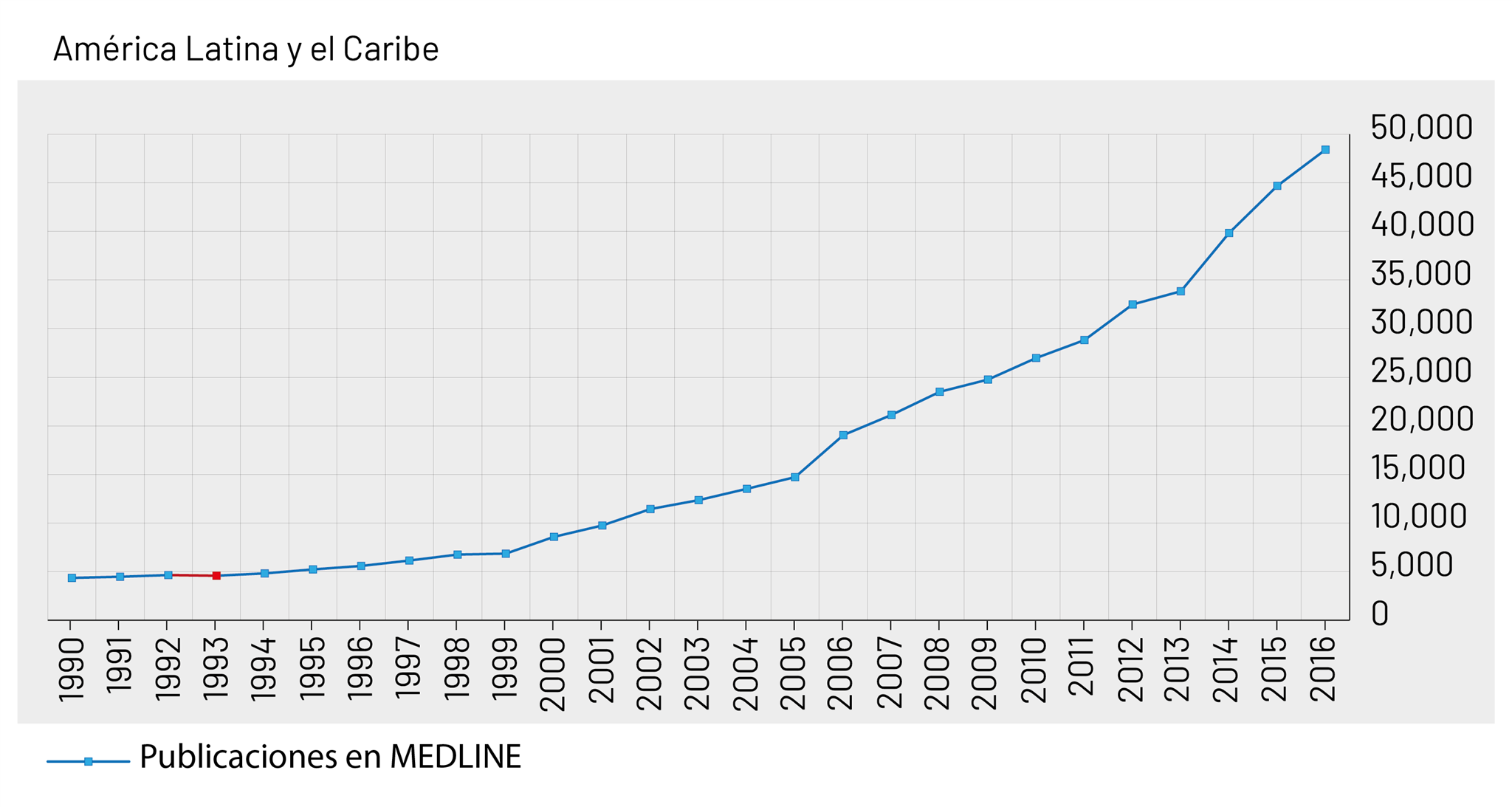

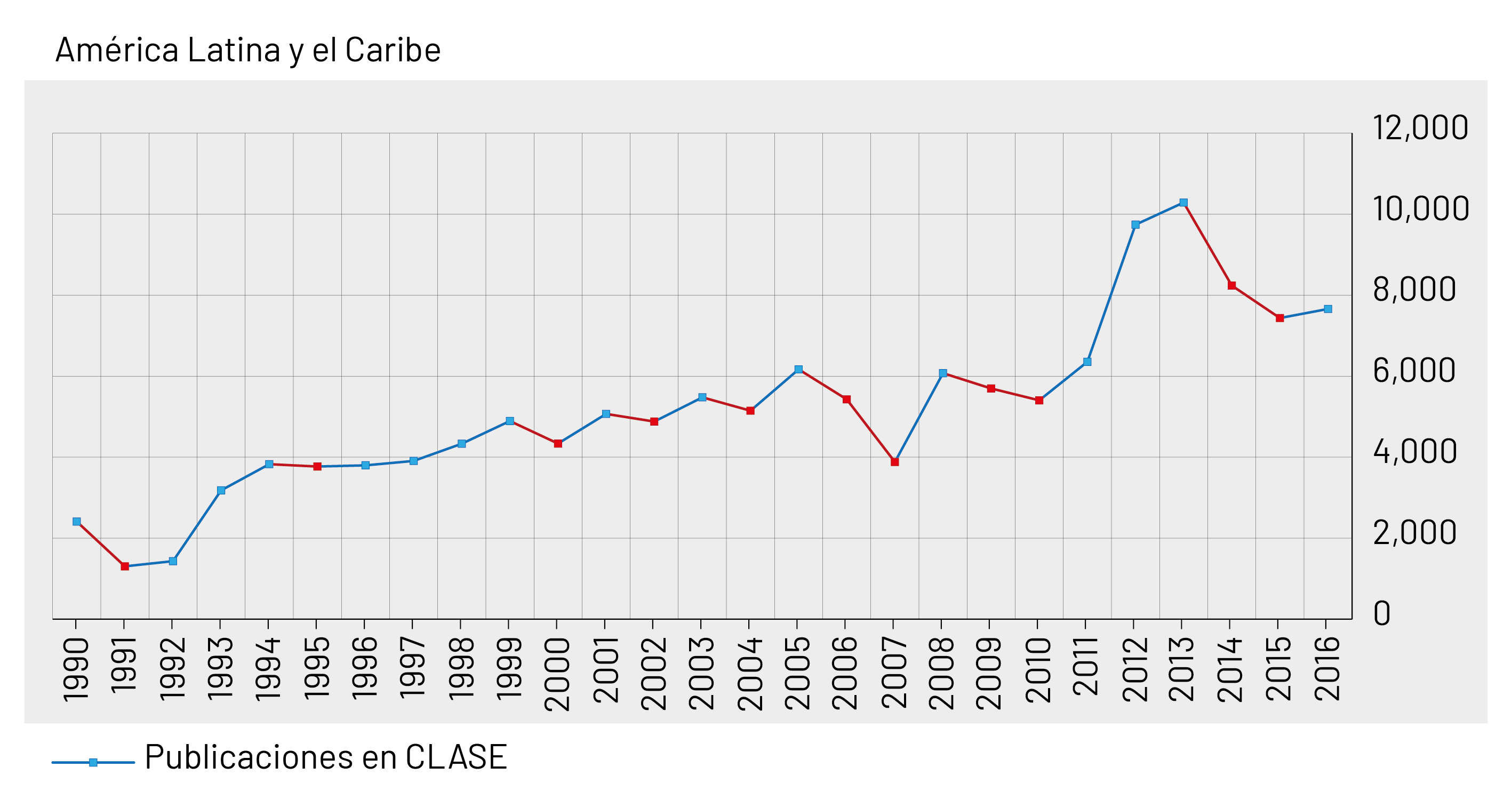

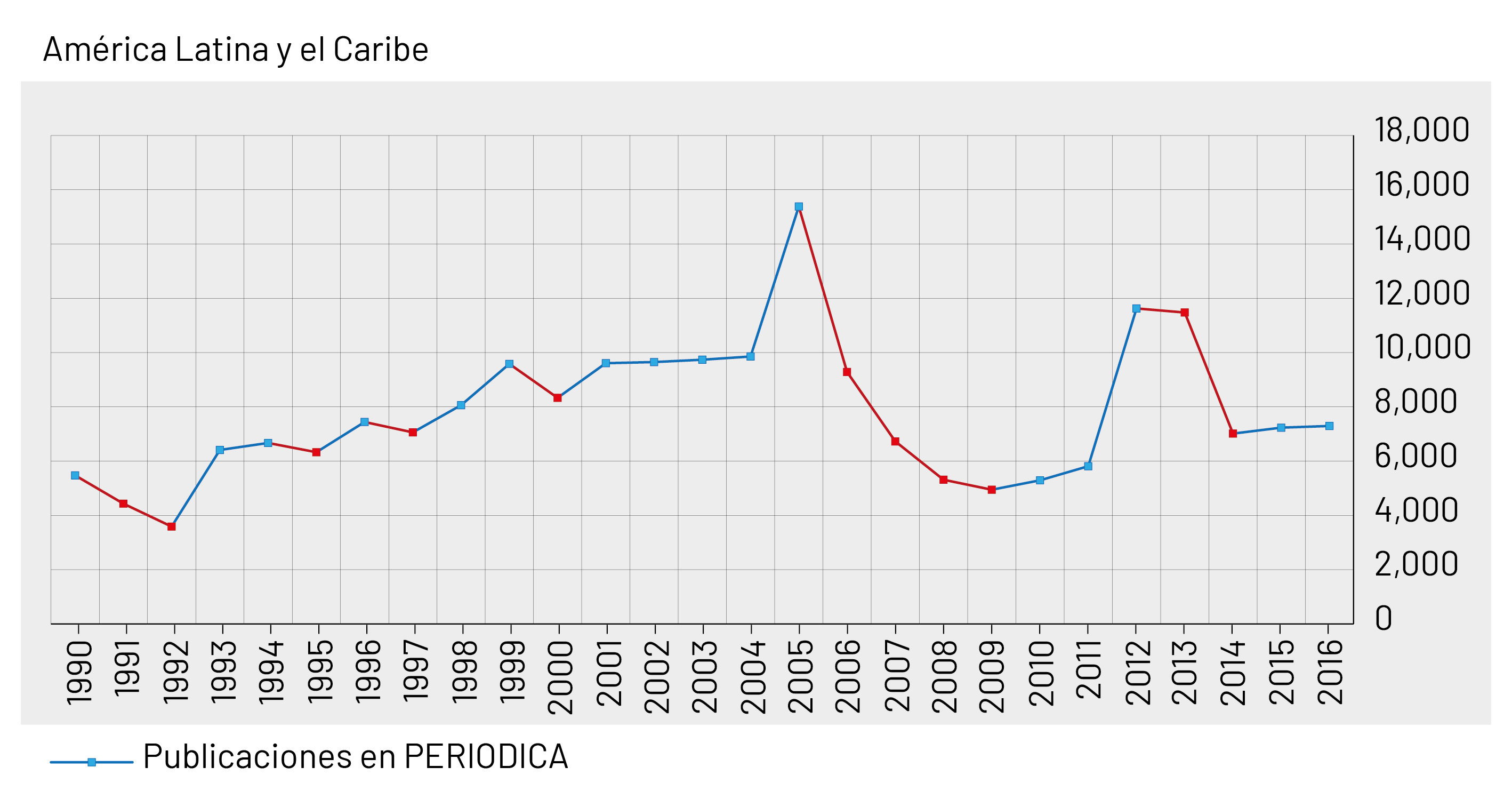

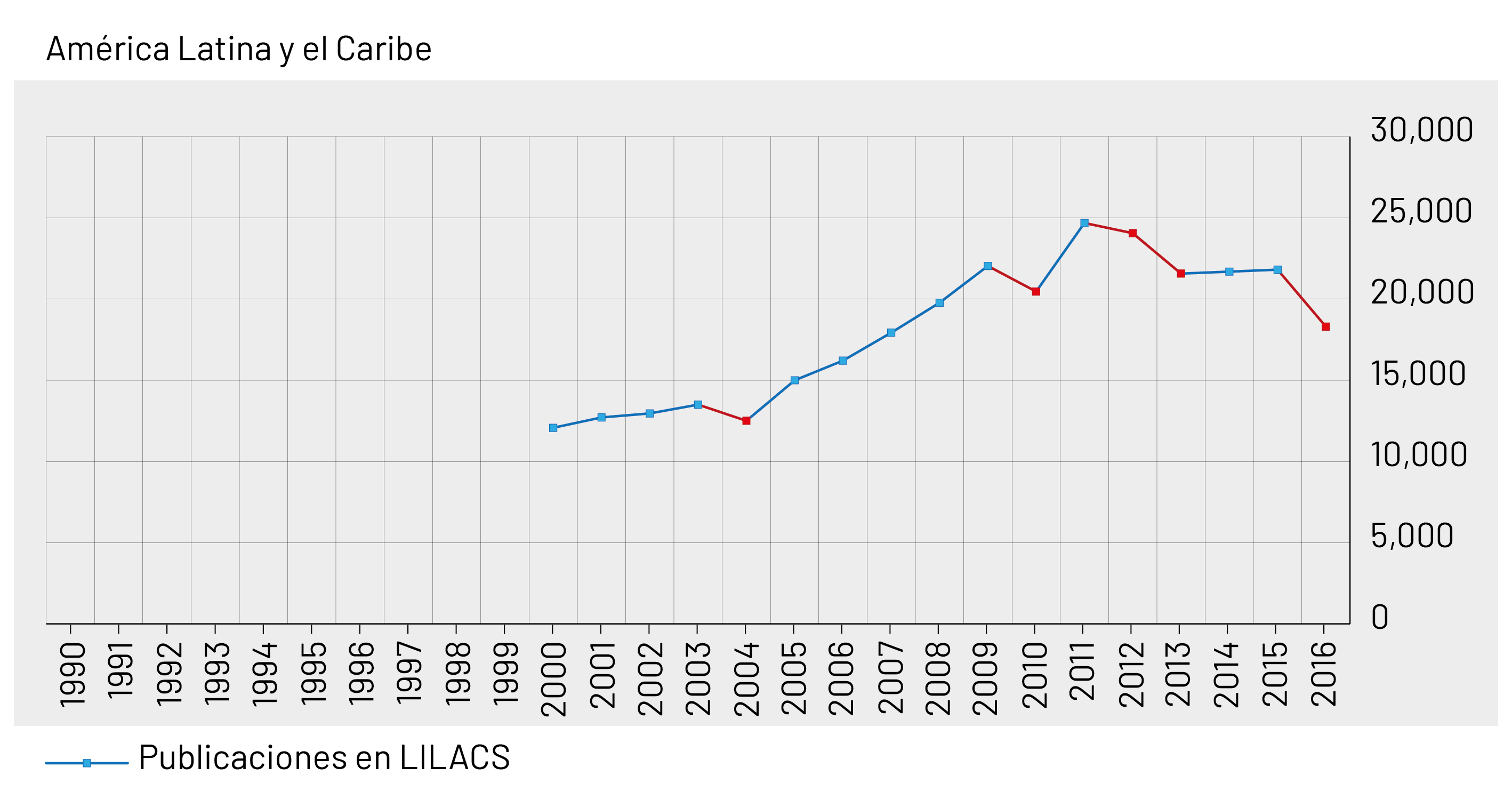

These data, for figures 1 (a, b, c) evince known aspects such as a greater presence in SCOPUS than in WoS and the weight of health science, but when compared to figures 2 (a, b, c,), it’s clear that despite the huge work of CLASE and PERIÓDICA (UNAM) and LILACS (BIREME), if we want a more real and complete picture of the region, it’d be necessary to consider from RICYT these other mentioned sources.

For instance, in general terms, though with fewer years of coverage, more recent projects are: until 2016, REDALYC reporting 547.162 articles and SCIELO, 469.919 articles. In specific terms, in the case of health, from REDALYC there were: Medicine (77.208 articles ) and Multidisciplinary Health (33.832 articles), and from SCIELO: Public Health (18.766 articles).

On the other hand, in terms of disciplines, it’d be worth to reconsider some other SIRes that would allow all disciplines to be taken into account, and allow more than one source option. For instance, referring to the work from Colombia mentioned above (no doubt there are equal and similar to this one in other countries), it recognises as sources for: Social Sciences 16 options, Humanities 6 options, Natural Science 12 options, Health Science and Medicine 8 options, Engineering and technology 2 options and Agricultural Science 1 option. Unfortunately though, our science organizations when finally “measuring and giving points” neither recognise nor give the same importance to all of them, neither generals nor disciplinaries, but this is a matter for another reflection.

With this text, there’s a call to consider from the next year onwards other general and disciplinary sources. We have to value, however, that our region has this resource by RICYT, which may be widen and enhanced in order to have a more comprehensive picture.

Alperin, J, P., & Fischman, G. (Ed.). (2015). Hecho en Latinoamérica: acceso abierto, revistas académicas e innovaciones regionales. Buenos Aires: CLACSO.