The Costs of APC: The case of Universidad de Antioquia

CoLav1

The costs of publishing in open access according to the European tendency of regulating its scientific publications market have caused a debate advising Latin America about the need to take a stance on the cost that policies such as Plan S could bring for science development and its circulation. Latin America has a groundbreaking proposal: a path for open science, as publications from the region were conceived in open access, where scientific production is created and circulated by the academy itself. Nonetheless, an important part of European and North American publications has not only charged for publishing, which they do more and more, but for accessing such articles as well. Such cost hasn’t been estimated for Latin America. What we want to show here is the publication costs of Universidad de Antioquia’s production, which is Colombia’s second most productive university and is among Latin America’s 50 most productive.

Latin America has a groundbreaking proposal: a path for open science, as publications from the region were conceived in open access, where scientific production is created and circulated by the academy itself.

In the 2017-2027 Institutional Development Plan, Universidad de Antioquia adopted open science as the guidelines that will guide the institution’s development over the decade. In this vein, the university approved in April 2018 the Open Access Policy to publications for the entity, it expresses that the institutional position is directed toward self-archiving in which the Sistema de Bibliotecas (Library System) plays a crucial role since it manages the university’s Institutional Repository where scientific production is collected as long as moral and patrimonial rights permit so.

However, where such policies have been socialized and disseminated it’s been evident that researchers are concerned about who is going to take the responsibility to finance publications in open access. Wondering who finances the Article Processing Charges (APC), automatically assuming that publishing in open access implies paying APCs to publishing houses, forgetting thus that there are other routes for open access which don’t require APC 2.

It is for this reason, among others, that the Universidad de Antioquia has commenced to developed strategies to measure and demystify open access within the Institution. In the first case, a research was carried out to calculate institutional practices in open access through sources and computing tools that CoLaV of UdeA (Universidad de Antioquia), a collaboratory that has been created in the university—has developed. In the second case, an awareness-raising campaign— UdeA abierta (“open UdeA”)—has been designed. Such campaign aims to introduce open access to the university’s actors, showing them its advantages, practices and the need to implement it in the institution.

This text aims to show advances in the first case, offering a global view of the Universidad de Antioquia case.

Methodology

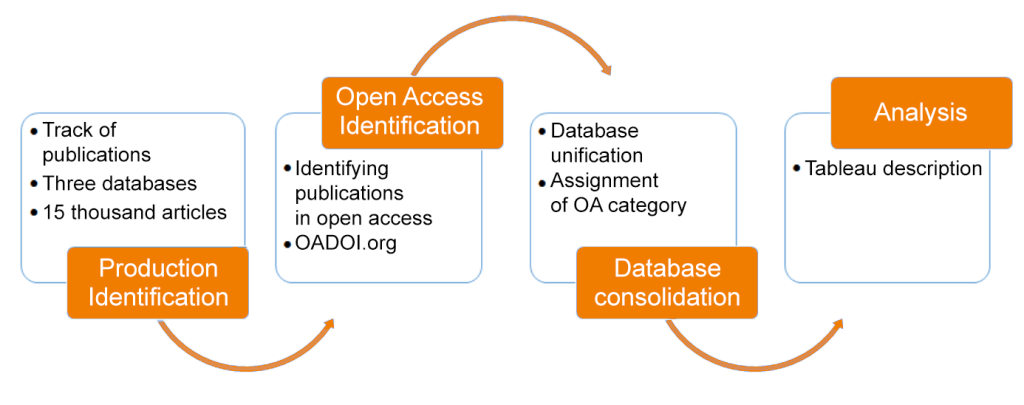

The university developed its own algorithm to identify scientific production in open access, it sought to include various available sources and then analyzed the information found. In all, 15.504 articles were identified, of which 7.990 had DOI, the study focused on the latter. The methodology is shown in the figure below (figure 1):

Figure 1. Diagnosis process for open access in UdeA

Data and Research

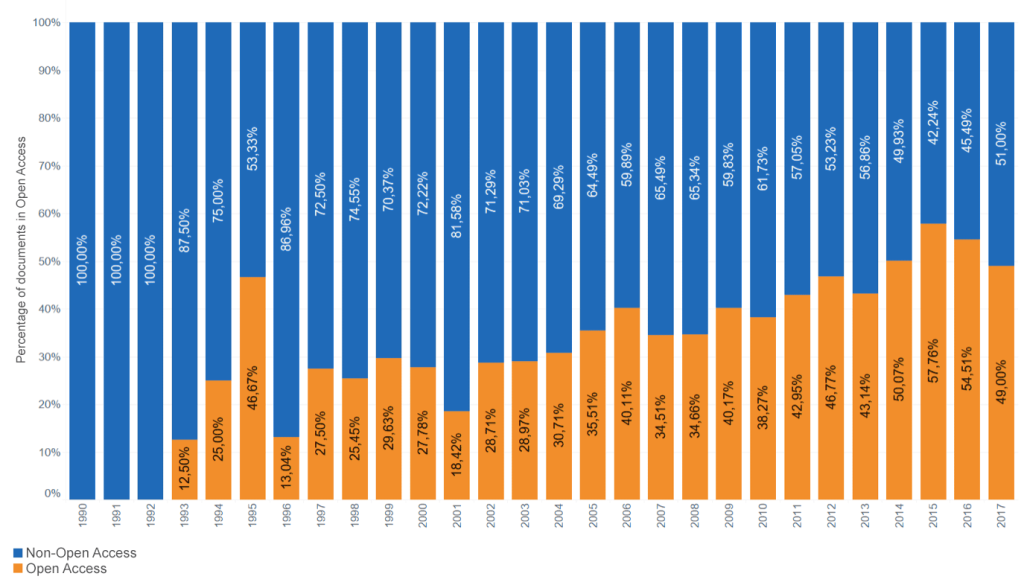

The university’s researchers haven’t needed an institutional policy to increase their interest for producing in open access. Figure 2 evinces how the percentage of production in open access in Universidad de Antioquia has increased. So, in this decade the amount is about 50% with an upward trend in the following years. Striking though is the fact that such data are considered up to 2017, in a context where there hasn’t been an institutional incentive clearly defined to promote open access. Thus, we could say of researchers that they do are sensitive to make their researches available.

Figure 2. Open access proportion in the UdeA per year

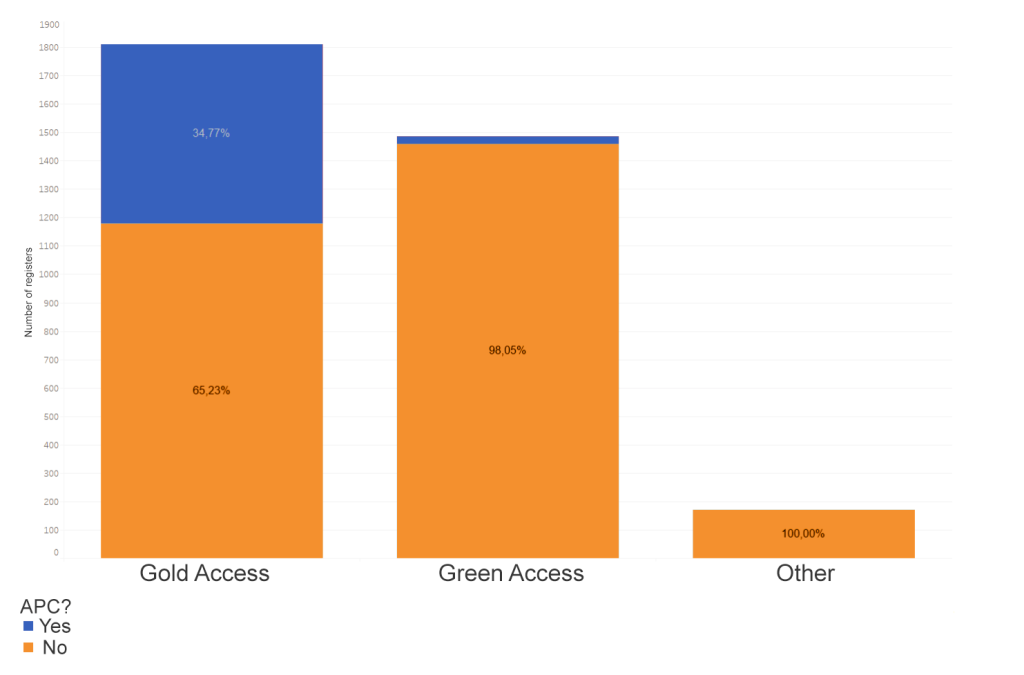

It is appropriate to show, in the figure below, how the production in open access is distributed (figure 3): A great amount of the university’s production is done in the gold route (52%), 43% in the green one (repositories) in the university whereas the other 5% in other routes such as hybrid open access. In the figure we see that 35% of production in orange has incorporated APCs, due to the available data it is not clear which institution payed, however.

Figure 3. Types of open access and payment of APCs in UdeA open access

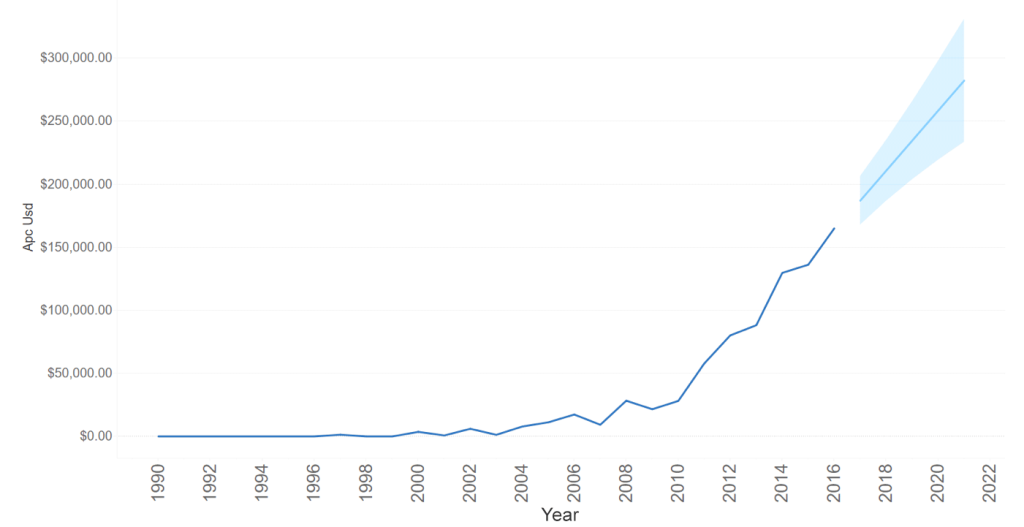

Hence, the interest to analyze how the payment of APCs works. Starting from 1990 to 2017, when USD$186,000 were paid, we use the exponential smoothing tecnique to forecast APCs values in the following years (figure 4). There’s clearly an increasing tendency in the amount of money that would be paid for the university’s publications, likely to reach USD$300,000 in 2022. Among other reasons this is why the temporal Committee of Open Science has worked to warn the university against this tendency so as to take policy actions according to the interests defined by the university.

Figure 4. Estimated and projected costs per publications with APCs of the UdeA.

Conclusion

In sum, a position must be taken, and that means taking a route such as Plan S or support a project such as AmeliCA. Both lead to open science, the first with high costs for Latin America in the path toward visibility, and the second one gives the academy the possibility to strengthen the circulation of its own production, taking charge of the costs cooperatively and not delegating the firm such possibility.

From the studies conducted so far on Open Access in Universidad de Antioquia we see how professors have been developing a culture, of their own accord and with no institutional incentives, inclined to publications that the university community freely makes available. Now, a linkage between open access and APCs has been identified, in the sense that the former necessarily implies the latter, which shouldn’t be like that. This is more the result of a publication dynamic out of habit and a lack of more knowledge about scientific communication and its various alternatives, which in this case is publishing in open access.

This is seen in the considerable increase of APCs in the university’s publications in recent years, and it’s forecast it’ll reach a similar value to the subscriptions that could be canceled to databases by the university. This should be a caveat not only for Universidad de Antioquia but for the group of Latin American institutions so that they address proactively the APCs matter and define the institutional position about it. Such should lead to strategies and decision-making to publish or not with APC, negotiate with the firms of databases a unified-integrated cost between access to database-open access-APC or canceling subscription as it’s already happening in various countries and universities (https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/?s=apc-https://bit.ly/2ZspOJ9), among others. In sum, a position must be taken, and that means taking a route such as Plan S or support a project such as AmeliCA. Both lead to open science, the first with high costs for Latin America in the path toward visibility, and the second one gives the academy the possibility to strengthen the circulation of its own production, taking charge of the costs cooperatively and not delegating the firm such possibility.

1 César Pallares, Alejandro Uribe Tirado, Gabriel Vélez Cuartas, Diego Restrepo, Jaider Ochoa, Huber Molina, David Medina.

2 See Open Access Journals free of charge APC: http://www.biblioteca.mincyt.gob.ar/revistas/apc