AmeliCA vs Plan S: Same target, two different strategies to achieve Open Access.

On 4 September 2018, a group of national research funding organisations, with the support of the European Commission and the European Research Council (ERC), announced the launch of cOAlition S, an initiative to make full and immediate Open Access to research publications a reality. It is built around Plan S, which consists of one target and 10 principles (Science Europe, 2019). Such target is that:

“By 2020 scientific publications that result from research funded by public grants provided by participating national and European research councils and funding bodies, must be published in compliant Open Access Journals or on compliant Open Access Platforms. “

Meanwhile in another region of the world AmeliCA was brewing, the extension of REDALYC’s philosophy, knowledge and technology to the Global South (Becerril-Garcia & Aguado-Lopez, 2018). Supported by UNESCOAmeliCA is a multi-institutional community-driven initiative that arises in response to the international, regional, national and institutional Open Access contexts, which looks for a collaborative, sustainable, protected and non-commercial solution for Open Knowledge in Latin America and the Global South (AmeliCA, 2018). This institution of Commons was launched at CLACSO’s conference on November 21, 2018, at the “UNESCO Special Forum: Democratization of academic knowledge. The challenges for open access to knowledge.“

We must first say that both initiatives—Plan S and AmeliCA—share the same target: to make Open Access a reality. However, Plan S and AmeliCA are two very different visions and conceptualizations regarding the circulation of scientific knowledge. What is their main difference? Notwithstanding they arose almost simultaneously and with the same goal, some of their proposed strategies are counterposed, how can it be?

It is necessary to explain a little bit about the history, culture and regional idiosyncrasies. Latin America has created and maintains a non-commercial structure where scientific publication belongs to academic institutions and not to large publishers. Each institution is part of an informal cooperative that has never been explicit; each institution finances journals with its own members, and then that content is available through Open Access to other institutions. Within this ecosystem, interoperability, visibility, and more recently, international standards, technology and innovation needs are covered by platforms such as CLACSO, Latindex, Redalyc, among others. This means that everyone gets the benefit of everyone’s investment. This kind of informal cooperation has worked even before Open Access obtained its official name from the Budapest Declaration.

Redalyc, for instance, has developed technology for the digital edition of scholarly journals, available for free for high-quality Latin American journals. Such is the case of Marcalyc, a web system for XML markup of scientific articles compliant with JATS standards that generates ePUB, HTML and PDF formats and an intelligent reader and mobile article reader as well, everything in an automated way. Moreover, it provides interoperability, visibility, metrics and other services

Neither fees for authors nor fees for readers have been included in the editorial tradition of the region. Open Access normally resides in institutional budgets, and for public universities this budget is found in national public funds. This means that public budgeting has played an important role in the circulation of scientific knowledge.

Now, AmeliCA revolves around strengthening editorial teams within academic institutions by providing technology and knowledge to ensure low costs in scholarly publishing which guarantees Open Access sustainability free of APCs. It also includes projects such as metrics for the evaluation of scientific work, OJS communities of users and developers, policies on copyright and use of licenses, XML JATS digital edition tools, among others.

Coincidentally, Plan S and AmeliCA are based on ten principles, which underline the strategies of each.On the one hand, Plan S focuses on regulating commercial agreements when APCs are involved; on the other, AmeliCA focuses on building an infrastructure from and for academic institutions.

Some proposals of Plan S and AmeliCA coincide, such as asserting that decisive steps must be taken to achieve Open Access. However it’s clear that the strategy of Plan S is regulatory and indicative, whereas AmeliCA proposes actions and projects in response to the issues faced when publishing and disseminating science.

For example, both initiatives recognize the problems of research assessment systems that provide incentives incorrectly based on indicators such as the impact Factor, and even both express their commitment to the principles of the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA, 2012). Nonetheless, AmeliCA has also organized a multidisciplinary working group of experts from various countries to generate metrics that are more relevant and fair for researchers, science and Open Access.

Plan S establishes a mandate and its fourth principle maintains that where applicable, Open Access publication fees are covered by the funders or universities, not by individual researchers. The mandates are not new, in Latin America there are more than 50, even so, does not a mandate guaranteeing the payment of APCs to publishers instead of securing investment for the development of academic infrastructure still maintains the nitty-gritty of the problem? Why not giving control of scientific publishing back to academic institutions? It seems that the objective is pursued with no intentions to affect the current corporate publishing structure that today stifles and opposes the objectives of openness and transparency and links its pricing scheme and sustainability to the control and manipulation of indicators criticized by everyone.

Although in regions like Latin America Open Access has been the natural form of scientific communication, this emerged as a concept in the Global North as a response to the high subscription costs to publications in the commercial oligopoly. Decade and a half later we observe that, as stated by Claudio Aspesi (2014): the finances of Elsevier and Wiley seem to be very healthy. Open Access has turned out to be a great business when subscription costs are transformed into costs for publishing.

However, restrictions on publishing for researchers in countries with scarce economic resources are increasing. Though Plan S proposes to establish APC levels and equitable waiver policies, the problem remains—the control of science is in the hands of a few and countries and their academic institutions have no control beyond commercial agreements. Waiver policies or establishing APC levels are disruptive mechanisms for systems that don’t operate under commercial or market rules as the one in Latin America.

Large publishers enjoy economies of scale which makes them “too big to fail” companies and can be considered natural monopolies that acquire a market power impeding competition. They reach an optimum level of production to produce more at lower cost. Nevertheless, overcrowding in the use of information and communication technologies provides the stage to break that power.

Furthermore, in order for a monopoly to exist, the company should exercise control over an indispensable resource to produce the product, and that other similar goods or services may not be found on the market to replace what’s offered by the monopolist. For scientific dissemination this indispensable resource is “quality legitimation” given by publications based on misused indicators that value the quality of research depending on the journal where it’s published.

Guédon (2017) rightly points out that scientific research has never been sustainable. Ever since the 17th century it has been heavily subsidized. The cost of communicating scientific research is a tiny fraction of the cost of doing research, somewhere in the region of 1% and 2%. So why should we look for that particular stage of research to be compliant with particular financial rules couched in terms of “sustainability” while most of scientific research has to be constantly subsidized?Why, partly because of the legacy of the print era. The digital world works differently.

n regions such as Latin America, scientific communication is supported by permanent institutional budgets, i.e. subsidized by institutions that generate science. AmeliCA, then, proposes a cooperative set of actions that leverage technology, knowledge and experience of multiple organizations so that scientific communication remains an activity in control of the academia averting the loss of those subsidies by not implementing commercial solutions of Open Access such as the APCs-based ones. AmeliCA works on optimization of available economic resources and processes to achieve sustainability.

Eurocentrism should, in the 21st century, acknowledge that there are other regions that do not necessarily share its vision and that Open Access concerns everyone, The Global South, however, is concerned that a model is being set up which again makes the South and North confront each other, in lieu of seeking to construct common platforms that use technologies for preventing henceforth the possibility of simply being controlled.

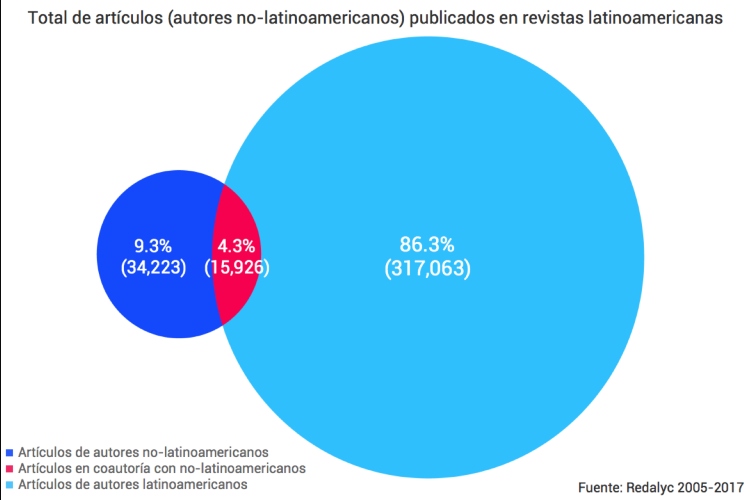

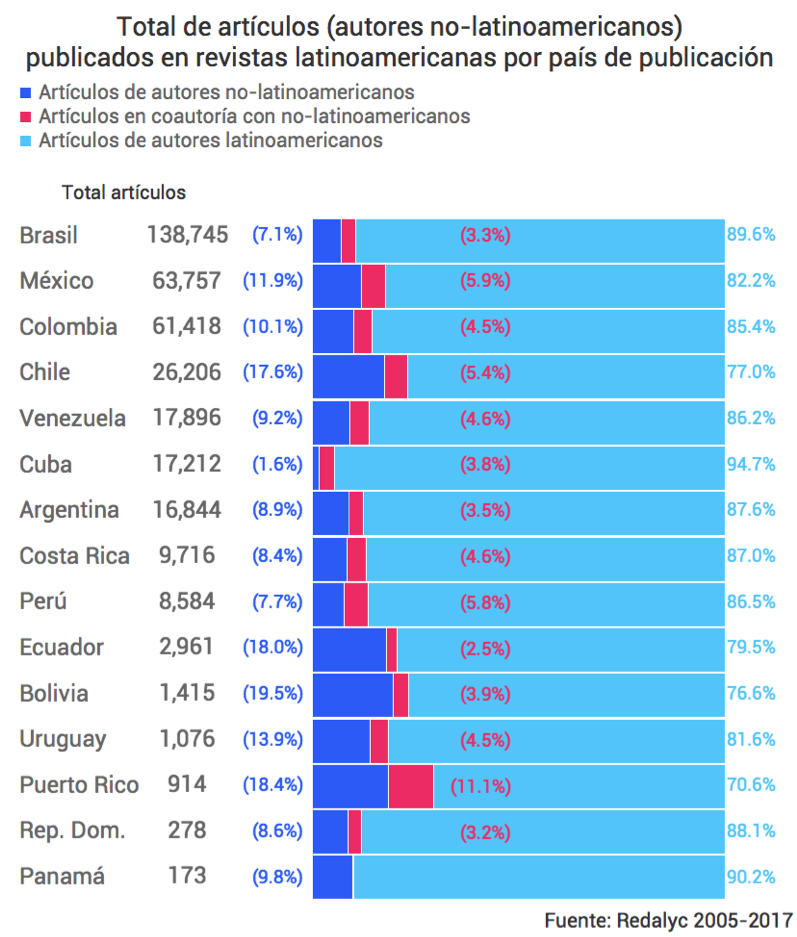

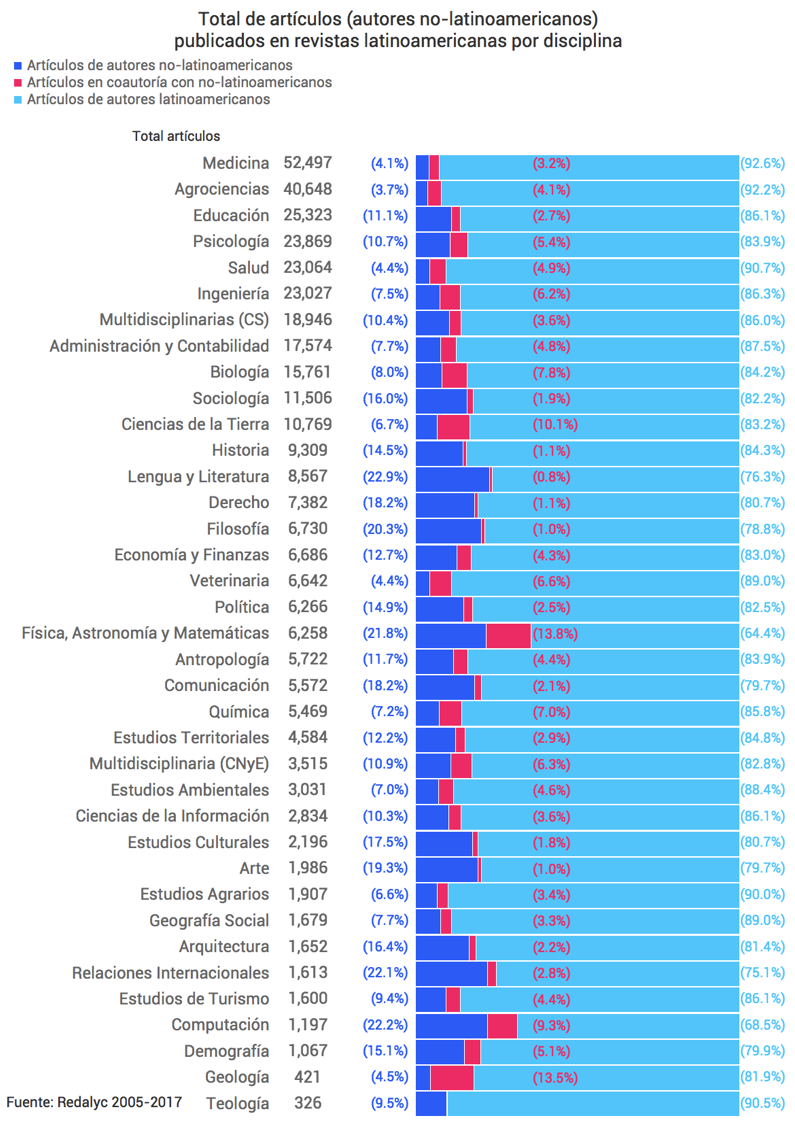

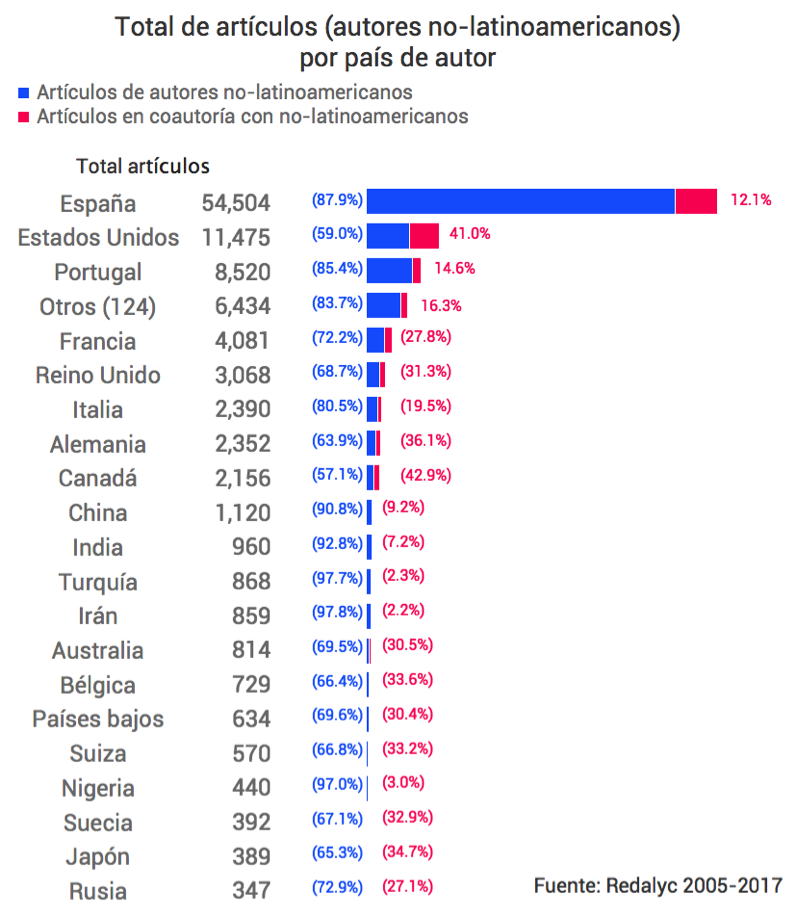

The scope of AmeliCA comprises the Global South in order to reinstate, strengthen and guarantee the sustainability of OA on the academia side and not on the commercial publishers’. Plan S considers not that its decisions alter scientific communication systems of other regions and other OA models. For example, what if a researcher from a country participating in Plan S wants to publish in a Latin American journal? Should Latin American journals then meet Plan S requirements, which are intended for journals published by commercial publishers? We must bear in mind that there are contributions from non-Latin American researchers published in journals from this region. Take REDALYC, where 13.6% of articles come from non-Latin American authors and at a country or field level 23% is represented by non-Latin American authors.

Science is a global institution and as such decisions and actions made at some point in the system influences and have consequences in other latitudes. We must seek as humanity a more equitable participation of all nations in the scientific discourse that comprehends local agendas, diversity and contributes in the reduction of gaps.

Bibliography

AmeliCA. (November 2018). AmeliCA Open Knowledge for Latin America and the Global South. Retrieved January 2019, from AmeliCA: http://www.amelica.org

Aspesi, C. (2014). Reed Elsevier: Goodbye to Berlin – The Fading Threat of Open Access (Upgrade to Market-perform). Bernstein Research, 1-20.

Becerril-Garcia, A., & Aguado-Lopez, E. (2018). The End of a Centralized open access Project and the Beginning of a Community-Based sustainable Infrastructure for Latin America: Redalyc.org after Fifteen years the open access ecosystem in Latin America. ELPUB. Toronto, Canada: HAL.

Dora. (2012). San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment. Retrieved from DORA: https://sfdora.org/

Guédon, J. (2017). Open Access: Towards the Internet of the Mind. Budapest Open Access Initiative.

Science Europe. (2019). Plan S. Retrieved January 2019, from https://www.coalition-s.org