Don’t you get it?! There’s no mainstream science in Social Sciences and Humanities!

Eduardo Aguado-López

As of the last decade of the previous century, journal assessment systems have been developed and consolidated. The methodological processes in assessment, though diverse, give differently weight to the variables involved. There’s a permanent variable, which virtually extends itself to all assessment systems: the indexing of journals in multiple systems. Nevertheless, in all assessment systems, indexing in the so-called mainstream science (WoS-Scopus) is the most important actor to consider a journal as international, high-quality, and representative, turning thus such indexing into legitimacy.

For example, in Sistema de Clasificación de Revistas del Conacyt 2016-2018 [“Conacyt’s Classification System of Journals”] (Mexico), the highest level—no need of assessment here—is occupied by journals indexed by such databases and are distributed according to the quartile they have in either system. Publindex (Colombia) does similarly. Incentive and productivity criteria for researchers in Ibero-American countries and around the world are established, perhaps, according to the venue of publication, determined by the Impact Factor (Clarivate Analytics) or Scimago Journal Rank (Scopus).

Having a global representative database of mainstream journals faces new challenges. It seems, though, it cannot be formed without the participation of ‘local-national-regional’ journals.

What’s noteworthy here is that indexing is a central characteristic in the system of science and that no substantial difference is made between Natural and Applied Sciences, on the one hand, and Social Sciences and Humanities, on the other. Homogenization affects, particularly and all the more, Social Sciences and Humanities for in recent decades the article became one of the central formats of communication because articles are more valued than books and monographs.

This is strongly and gradually asserted, Rosa García Ruiz puts it like this: “Consequently, prestigious scientific journals are recognized by their place in databases, for instance Comunicar is found in more than 650 databases, though (…) those databases that index journals considering different variables regarding their impact, may be deemed as more important and prestigious, hence, a debatable quality index is given to them within the set of journals of the same category. A clear example of such databases is Scopus or Web of Science.”

The biases of WoS and Scopus have been widely recoded: (a) language; (b) geography; (c) field of knowledge; (d) discipline; albeit recognized, when talking about Social and Human Sciences such biases are intensified by the sheer fact that Social Sciences and Humanities are strongly under-represented in such bases.

Let us take a look into the participation of Social Sciences and Humanities in three different areas:

-

1. Amount of journals. Here, under-representation is crystal-clear in SJR-Scopus. One out of three journals pertains to the Social Sciences and Humanities, whereas in Journal Citation Report from Web of Science of Clarivate almost 1 out of four journals belongs to such fields. The greatest weight of Scopus is explained because it seeks to surpass WoS with its politics of space and competitiveness, it gave more space to disciplines and regions that weren’t included, adopting inclusion as a marketing strategy. In all, in SJR-Scopus there are 8,49 journals out of 24,228, whereas in JCR-WoS there are solely 3,312 out of 12,327 journals.

Due the differences on periodicity and number of articles per issue, the number of journals is not necessarily a good indicator to account for the weight fields, countries or institutions may have. Diversity has been intensified with the emergence of periodical journals and the arrival of ‘megajournals.’ As Spezi and colleagues’ work, reviewed by Universo Abierto, state, even though they constitute a small portion in terms of numbers, they represent roughly 2.5% of scientific articles in 2015. For example, in 2015 PLOS published upwards of 27 thousand articles, Scientific Reports little more than 10 thousand, among others. When millions of articles are published per year, the weight of fields and disciplines is to be sought and identified through the number of quotable documents.

-

Quotable documents. Quotable articles included in SJR-Scopus journals amount to more than 16 million of which only 1,272,775, i.e. 7.7% pertain to Social Sciences and Humanities. In other words, less than one out of ten quotable scientific articles pertain to Social Sciences and Humanities. As to JCR uploads scarcely 1 out of 10 (10.8%), though, since half of journals are from SJR-Scopus, it only has 178,120 quotable articles. Is it possible to identify work, productivity, relevance and impact of Social Sciences and Humanities in databases that clearly do not gather the output of such areas, not even numerically, thematically and geographically?

According to UNESCO Science Report: Towards 2030, there are roughly 8 million researchers in the world, 5 regions and countries have 72% of them: European Union (22.2%); China (19.1%); USA (16.7%); Japan (8.5%) and Russia (5.7%). The number of articles is much smaller than that of researchers, yet perspectives would change if the number of articles from peer-reviewed journals identified around the globe were considered.

-

Citations. In the last decades, they have become the ultimate indicator of success, prestige and quality of a work. The indicator proposed to help librarians identify journals used by the academic community through references—citations—to gain subscriptions and which generated the Impact Factor (citations among articles within a period of time) has become, unfortunately, the main indicator to assess individuals and institutions. Although, in recent years, citation databases of open access have appeared (Google citations, Dimensions, Cross Ref., etc.), the databases that have become famous for giving citations are WoS and Scopus. Knowing the number of citations per field it’s important because, based on that, success of publications is discerned.

Citations in Social Sciences and Humanities in SJR-Scopus amount to 15%, that is, 1.5 out of 10 pertain to such fields, and JCR-Clarivate has fewer citations: one out of ten pertains to Social Sciences and Humanities, this is, quite obviously, insufficient.

Social and Human Sciences work with social facts, that is, social constructions in which context, history, values are central factors in their establishment. Hence, national and local studies become increasingly more relevant, not because such are ‘parishioner’ or ‘nationalist’ fields, but rather because of the specificity of their own object of study.

In terms of numbers, we see the insufficiency and under-representation of the so-called mainstream science for Social Sciences and Humanities. Is it, then, appropriate to determine the work of researchers by virtue of their output or citation in such databases? Let us consider a particular case: national researchers of excellence in Mexico: members of the Sistema Nacional de Investigación [“National System of Research”] (SNI) of the Consejo de Ciencia y Tecnología [“Council of Science and Technology”] (CONACYT). “SNI is synonymous with prestige for it represents a select group that distinguishes researchers who carry out their work more efficiently and make remarkable contributions to knowledge, from an economic stance, such system means ‘supplemental wages.’ (Rodríguez Miramontes, et. al. 2017). (Rodríguez Miramontes, et. al. 2017).

At present, there are around 28 thousand SNI researchers—it is considered that SNI represents roughly 33% of the national overall (Rodríguez, 2016), distributed in 8 fields of knowledge of which 2 pertain to Social Sciences and Humanities: field V. Social Sciences and field IV. Humanities and Behavioral Science. In all, they have 31% SNI researchers in 2015 (Cabrero, 2015).

many national researchers work for Scopus, the results may be surprising, and though there aren’t many researches that serve to give a precise answer, the Foro Consultivo de Ciencia y Tecnología [“Advisory Forum of Science and Technology”] (FCCyT) carried out a research conducted by Dutrénit, et. al. (2014) that allows us know, precisely, such situation, the results—from Scopus—are shocking:

-

SNI members produced less than 70% out of the production by Mexican researchers in Scopus in 2009 (67.9%);

-

Participation decreased from 74.5% in 2003 to 67.9% in 2009;

-

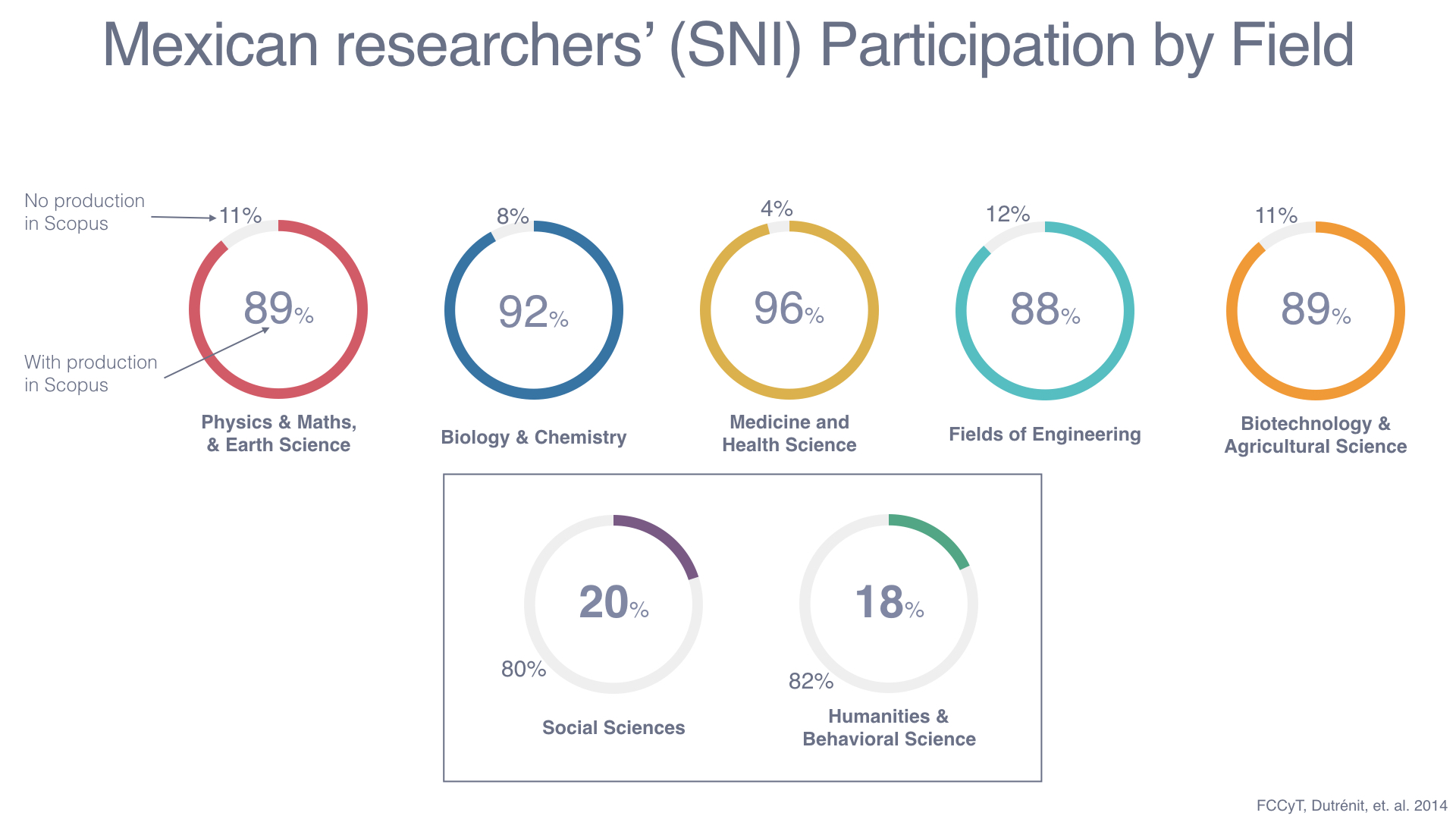

3. For Natural and Applied Sciences, virtually every researcher has articles in Scopus: the smaller amount is 88-89% regarding the Physics and Mathematics field and Earth Science, Engineering and Biotechnology and Agricultural Sciences.

-

More than 92% of Biology and Chemistry researchers have documents in Scopus;

-

5. Medicine and Health Science is the best field represented in Scopus, 96% of researchers have their scientific output in such database;

-

6. In Social Sciences and Humanities things are quite the opposite, SNI researchers don’t have a significant amount of scientific output in Scopus;

-

Only 20% of researchers on Social Sciences, members of SNI, had at least one article in Scopus;

-

Only 18% of researchers on Humanities and Behavioral Science had one article in Scopus; (Dutrénit, et. al. 2014).

Using a non-representative database for almost 30% of national researchers on Social Sciences and Humanities results in:

-

a) Underestimating the global participation of a country or institution due the under-representation of journals and output of such fields;

-

b) An inaccurate image about the participation and productivity of Social Sciences and Humanities regarding generation and dissemination of knowledge, seen as an image of low productivity and unawareness of the real impact Social and Human Sciences have in the generation of knowledge and in society

There are several aspects that make considering the making of a representative database for Social Sciences and Humanities at a global scale something that will face new challenges:

Simply put, Natural and Applied Sciences study nature and natural phenomena, which are global, whereas Social Sciences and Humanities study human beings, society and its ins

titutions, they try to explain and comprehend how the social world operates. While Natural and Applied Sciences work with ‘natural’ facts independent of human beings, though affected by them, Social and Human Sciences work with social facts, that is, social constructions in which context, history, values are central factors in their establishment. Hence, national and local studies become increasingly more relevant, not because such are ‘parishioner’ or ‘nationalist’ fields, but rather because of the specificity of their own object of study.

This is no place for an epistemic discussion, but think of family, values, poverty, democracy, peace, inclusion, inequality, freedom adhesion, rebellion, migration, emigration, corruption, ethics, just to mention some fields. It’s not possible to study sexuality, gender, roles, and diversity but through a socio-cultural context that explains and conditions it. These ‘loaded’ topics aren’t the only ones that are contextual and historic, but also socio-economic phenomena such as migration and the way different societies take it in.

Having a global representative database of mainstream journals faces new challenges. It seems, though, it cannot be formed without the participation of ‘local-national-regional’ journals. the way in which, over decades, social scientists have published, beyond the pressure of institutionalized assessment that favor some databases more than others.

1. In 2013, 30% of researchers belonged to areas IV and V http://www.atlasdelacienciamexicana.org/sni/fig68.png

Methodology (Participation of Social Sciences in SJR and JCR)

Information was downloaded around November 16th and 20th, 2018.

-

-

- To obtain Scimago Journal Rank (SJR) indicators these sites were consulted:

- The whole list of journals was downloaded and data from SJR were used. Countries and fields were assigned according to information from Cite Core and the list of sources of Scopus.

- Journals participating in more than one field have the same indicators.

- The Social Sciences and Humanities group is composed of the following: Arts and Humanities, Business, Management and Accounting, Decision Sciences, Economics, Econometrics and Finance, Psychology, Social Sciences.

- The Latin American region groups the following: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, Puerto Rico, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay and Venezuela.

- Iberian Peninsula: Spain and Portugal.

- Indicators are:

- Journals: Amount of indexed journals in 2018.

- Quotable documents: Quotable documents published in 2014, 2015 and 2016 (any type of documents are considered).

- Total quotes: Amount of quotes received in 2017 to published documents in 2014, 2015 and 2016 (any type of documents are considered).

- To obtain Journal Citations Reports (JCR) indicators the following sites were consulted:

- The whole list with data of JCR journals was downloaded. Country was assigned with information by Master List of Web Science.

- Journals taking part in more than one edition have the same indicators.

- SSCI corresponds to Social Sciences and SCIE to Natural and Applied Sciences.

- The Latin American region groups the following: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Venezuela.

- Iberian Peninsula: Spain and Portugal.

- Indicators used:

- Journals: Amount of indexed journals in 2018.

- Quotable documents: Quotable documents published in 2016 and 2015.

- Total quotes: total quotes obtained in 2017 for all years of publication.

-

References

Cabrero, E. (2015). “Principales logros y desafíos del Sistema Nacional de Investigadores de México a 30 años de su creación”. Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencia, Tecnología y Sociedad – CTS, 10 (28), 1-12. Available at: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/924/92433772013.pdf

Dutrénit G., Zaragoza M. & Zúñiga P. (2014). “La producción científica del Sistema Nacional de Investigadores de México: un análisis con la base de datos normalizada de SCOPUS”. Taller sobre indicadores en ciencia y tecnología en América Latina, pp.165-180.

Rodríguez, C. E. (2016). El sistema nacional de investigadores en números. Mexico: Foro Consultivo y Tecnológico. Available at: dehttp://www.foroconsultivo.org.mx/libros_editados/SNI_en_numeros.pdf

Rodríguez J., González C, & Maqueda G. (2017). El Sistema Nacional de Investigadores en México: 20 años de producción científica en las instituciones de educación superior (1991-2011). Library Science Research, 31(spe), pp.187-219. Available at: https://dx.doi.org/10.22201/iibi.24488321xe.2017.nesp1.57890

Spezi V, Wakeling S, Pinfield S, CreaserS, Fry J, & Willett P, (2017) “Open-access mega-journals: The future of scholarly communication or academic dumping ground? A review”, Journal of Documentation, Vol. 73 (2), pp.263-283. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-06-2016-0082